Revision Auswahl

Git allows you to specify specific commits or a range of commits in several ways. They aren’t necessarily obvious but are helpful to know.

Git erlaubt dir, Commits auf verschiedenste Art und Weise auszuwählen. Diese sind nicht immer offensichtlich, aber es ist hilfreich diese zu kennen.

Single Revisions

Einzelne Revisionen

You can obviously refer to a commit by the SHA-1 hash that it’s given, but there are more human-friendly ways to refer to commits as well. This section outlines the various ways you can refer to a single commit.

Du kannst offensichtlich mithilfe des SHA-1 hash einen commit auswählen, aber es gibt auch Menschen freundlichere Methoden auf ein commit zu verweisen. Dieser Bereich skizziert die verschiedenen Wege, die man gehen kann um auf ein einzelnen commit zu referenzieren.

Short SHA

Abgekürztes SHA

Git is smart enough to figure out what commit you meant to type if you provide the first few characters, as long as your partial SHA-1 is at least four characters long and unambiguous — that is, only one object in the current repository begins with that partial SHA-1.

Git ist intelligent genug, den richtigen commit herauszufinden, wenn man nur die ersten paar Zeichen angibt aber nur unter der Bedingung, dass der SHA-1 hash mindestens vier Zeichen lang und einzigartig ist — das bedeutet, dass es nur ein Objekt im derzeitigen Repository gibt, das mit diesem bestimmten SHA-1 hash beginnt.

For example, to see a specific commit, suppose you run a git log command and identify the commit where you added certain functionality:

Um zum Beispiel einen bestimmten commit zu sehen, kann man das git log Kommando ausführen und den commit identifizieren in dem man eine bestimmte Funktionalität hinzugefügt hat:

$ git log

commit 734713bc047d87bf7eac9674765ae793478c50d3

Author: Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com>

Date: Fri Jan 2 18:32:33 2009 -0800

fixed refs handling, added gc auto, updated tests

commit d921970aadf03b3cf0e71becdaab3147ba71cdef

Merge: 1c002dd... 35cfb2b...

Author: Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com>

Date: Thu Dec 11 15:08:43 2008 -0800

Merge commit 'phedders/rdocs'

commit 1c002dd4b536e7479fe34593e72e6c6c1819e53b

Author: Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com>

Date: Thu Dec 11 14:58:32 2008 -0800

added some blame and merge stuffIn this case, choose 1c002dd.... If you git show that commit, the following commands are equivalent (assuming the shorter versions are unambiguous):

In diesem Fall wählt man 1c002dd.... wenn du diesen commit mit git show anzeigen lassen willst, die folgenden Kommandos sind äquivalent (vorausgesetzt die verkürzte Version ist einzigartig):

$ git show 1c002dd4b536e7479fe34593e72e6c6c1819e53b

$ git show 1c002dd4b536e7479f

$ git show 1c002dGit can figure out a short, unique abbreviation for your SHA-1 values. If you pass --abbrev-commit to the git log command, the output will use shorter values but keep them unique; it defaults to using seven characters but makes them longer if necessary to keep the SHA-1 unambiguous:

Git kann auch selber eine Kurzform für deine einzigartigen SHA-1 Werte erzeugen. Wenn du --abbrev-commit dem git log Kommando übergibst, wird es den kürzeren Wert benutzen diesen aber einzigartig halten; die Standardeinstellung sind sieben Zeichen aber es werden automatisch mehr benutzt wenn dies nötig ist um den SHA-1 hash eindeutig zu bezeichnen.

$ git log --abbrev-commit --pretty=oneline

ca82a6d changed the version number

085bb3b removed unnecessary test code

a11bef0 first commitGenerally, eight to ten characters are more than enough to be unique within a project. One of the largest Git projects, the Linux kernel, is beginning to need 12 characters out of the possible 40 to stay unique.

Generell kann man sagen das acht bis zehn Zeichen mehr als ausreichend in einem Projekt sind, um eindeutig zu bleiben. Eines der größten Git Projekte, der Linux kernel, fängt langsam an 12 von maximal 40 Zeichen zu nutzen um eindeutig zu bleiben.

A SHORT NOTE ABOUT SHA-1

EINE KURVE NOTIZ ÜBER SHA-1

A lot of people become concerned at some point that they will, by random happenstance, have two objects in their repository that hash to the same SHA-1 value. What then?

Eine Menge Leute machen sich Sorgen, dass ab einem zufälligen Punkt zwei Objekte im Repository vorhanden sind, die den gleichen SHA-1 hash wert haben. Was Dann?

If you do happen to commit an object that hashes to the same SHA-1 value as a previous object in your repository, GIt will see the previous object already in your Git database and assume it was already written. If you try to check out that object again at some point, you’ll always get the data of the first object.

Wenn es passiert, dass bei einem commit, ein Objekt mit dem gleichen SHA-1 hash Wert im Repository vorhanden ist, wird Git sehen, dass das vorherige Objekt bereits in der Datenbank vorhanden ist und davon ausgehen, dass es bereits geschrieben wurde. Wenn du versuchst das Objekt später wieder auszuchecken wirst du immer die Daten des ersten Objekts bekommen.

However, you should be aware of how ridiculously unlikely this scenario is. The SHA-1 digest is 20 bytes or 160 bits. The number of randomly hashed objects needed to ensure a 50% probability of a single collision is about 2^80 (the formula for determining collision probability is p = (n(n-1)/2) * (1/2^160)). 2^80 is 1.2 x 10^24 or 1 million billion billion. That’s 1,200 times the number of grains of sand on the earth.

Allerdings solltest du dir bewusst machen wie unglaublich unwahrscheinlich dieses Szenario ist. Die Länge des SHA-1 hashs beträgt 20 bytes oder 160bits. Die Anzahl der Objekte die benötigt werden, um eine 50% Chance einer Kollision zu haben, beträgt ungefähr 2^80 (die Formel zum berechnen der Kollisionswahrscheinlichkeit lautet ‚p = (n(n-1)/2) * (1/2^160))‘. 2^80 ist somit 1.2 x 10^24 oder eine Trilliarden. Das ist 1200 mal die Anzahl der Sandkörner die es auf der Erde gibt.

Here’s an example to give you an idea of what it would take to get a SHA-1 collision. If all 6.5 billion humans on Earth were programming, and every second, each one was producing code that was the equivalent of the entire Linux kernel history (1 million Git objects) and pushing it into one enormous Git repository, it would take 5 years until that repository contained enough objects to have a 50% probability of a single SHA-1 object collision. A higher probability exists that every member of your programming team will be attacked and killed by wolves in unrelated incidents on the same night.

Hier ist ein Beispiel welches dir eine Vorstellung davon geben wird was nötig ist um in SHA-1 eine Kollision zu bekommen. Wenn alle 6,5 Milliarden Menschen auf der Erde Programmieren würden und jeder jede Sekunde Code schreiben würde, der der gesamten Geschichte des Linux Kernels (1 Millionen Git Objekte) entspricht und diesen dann in ein gigantisches Git Repository übertragen würden, würde es fünf Jahre dauern bis das Repository genügend Objekte hätte um eine 50% Wahrscheinlichkeit für eine einzige SHA-1 Kollision aufzuweisen. Es ist wahrscheinlicher das jedes Mitglied deines Programmierer Teams, unabhängig voneinander, in einer Nacht von Wölfen angegriffen und getötet wird.

Branch References

Branch Referenzen

The most straightforward way to specify a commit requires that it have a branch reference pointed at it. Then, you can use a branch name in any Git command that expects a commit object or SHA-1 value. For instance, if you want to show the last commit object on a branch, the following commands are equivalent, assuming that the topic1 branch points to ca82a6d:

Am direktesten kannst du einen Commit spezifizieren, wenn eine Branch Referenz direkt auf ihn zeigt. In dem Fall kannst du in allen Git Befehlen, die ein Commit Objekt oder einen SHA-1 Wert erwarten, statt dessen den Branch Namen verwenden. Wenn du z.B. den letzten Commit in einem Branch sehen willst, sind die folgenden Befehle äquivalent (vorausgesetzt der topic1 Branch zeigt auf den Commit ca82a6d):

$ git show ca82a6dff817ec66f44342007202690a93763949

$ git show topic1If you want to see which specific SHA a branch points to, or if you want to see what any of these examples boils down to in terms of SHAs, you can use a Git plumbing tool called rev-parse. You can see Chapter 9 for more information about plumbing tools; basically, rev-parse exists for lower-level operations and isn’t designed to be used in day-to-day operations. However, it can be helpful sometimes when you need to see what’s really going on. Here you can run rev-parse on your branch.

Wenn du sehen willst, auf welchen SHA-1 Wert ein Branch zeigt, oder wie unsere Beispiele intern in SHA-1 Werte übersetzt aussähen, kannst du den Git Plumbing Befehl rev-parse verwenden. In Kapitel 9 werden wir genauer auf Plumbing Befehle eingehen. Kurz gesagt ist rev-parse als eine Low-Level Operation gedacht und nicht dafür, im tagtäglichen Gebrauch eingesetzt zu werden. Aber es kann manchmal hilfreich sein, wenn man wissen muß, was unter der Haube vor sich geht:

$ git rev-parse topic1

ca82a6dff817ec66f44342007202690a93763949RefLog Shortnames

RefLog Kurznamen

One of the things Git does in the background while you’re working away is keep a reflog — a log of where your HEAD and branch references have been for the last few months.

Eine andere Sache, die während deiner täglichen Arbeit im Hintergrund passiert ist, daß Git ein sogenanntes Reflog führt, d.h. ein Log darüber, wohin deine HEAD und Branch Referenzen in den letzten Monaten jeweils gezeigt haben.

You can see your reflog by using git reflog:

Du kannst das Reflog mit git reflog anzeigen:

$ git reflog

734713b... HEAD@{0}: commit: fixed refs handling, added gc auto, updated

d921970... HEAD@{1}: merge phedders/rdocs: Merge made by recursive.

1c002dd... HEAD@{2}: commit: added some blame and merge stuff

1c36188... HEAD@{3}: rebase -i (squash): updating HEAD

95df984... HEAD@{4}: commit: # This is a combination of two commits.

1c36188... HEAD@{5}: rebase -i (squash): updating HEAD

7e05da5... HEAD@{6}: rebase -i (pick): updating HEADEvery time your branch tip is updated for any reason, Git stores that information for you in this temporary history. And you can specify older commits with this data, as well. If you want to see the fifth prior value of the HEAD of your repository, you can use the @{n} reference that you see in the reflog output:

Immer dann, wenn ein Branch in irgendeiner Weise aktualisiert wird oder du den aktuellen Branch wechselst, speichert Git diese Information ebenso im Reflog wie Commits und anderen Informationen. Wenn du wissen willst, welches der fünfte Wert vor dem HEAD war, kannst du die @{n} Referenz angeben, die du in Reflog Ausgabe sehen kannst:

$ git show HEAD@{5}You can also use this syntax to see where a branch was some specific amount of time ago. For instance, to see where your master branch was yesterday, you can type

Außerdem kannst du dieselbe Syntax verwenden, um eine Zeitspanne anzugeben. Um z.B. zu sehen, wo dein master Branch gestern war, kannst du eingeben:

$ git show master@{yesterday}That shows you where the branch tip was yesterday. This technique only works for data that’s still in your reflog, so you can’t use it to look for commits older than a few months.

Das zeigt dir, wo der master Branch gestern war. Diese Technik funktioniert nur mit Daten, die noch im Reflog sind, d.h. man kann sie nicht für Commits verwenden, die ein älter sind als ein paar Monate.

To see reflog information formatted like the git log output, you can run git log -g:

Um Reflog Informationen in einem Format wie in git log anzeigen, kannst du git log -g verwenden:

$ git log -g master

commit 734713bc047d87bf7eac9674765ae793478c50d3

Reflog: master@{0} (Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com>)

Reflog message: commit: fixed refs handling, added gc auto, updated

Author: Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com>

Date: Fri Jan 2 18:32:33 2009 -0800

fixed refs handling, added gc auto, updated tests

commit d921970aadf03b3cf0e71becdaab3147ba71cdef

Reflog: master@{1} (Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com>)

Reflog message: merge phedders/rdocs: Merge made by recursive.

Author: Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com>

Date: Thu Dec 11 15:08:43 2008 -0800

Merge commit 'phedders/rdocs'It’s important to note that the reflog information is strictly local — it’s a log of what you’ve done in your repository. The references won’t be the same on someone else’s copy of the repository; and right after you initially clone a repository, you’ll have an empty reflog, as no activity has occurred yet in your repository. Running git show HEAD@{2.months.ago} will work only if you cloned the project at least two months ago — if you cloned it five minutes ago, you’ll get no results.

Es ist wichtig zu verstehen, daß das Reflog ausschließlich lokale Daten enthält. Es ist ein Log darüber, was du in deinem Repository getan hast, und es ist nie dasselbe wie in einem anderen Clone des selben Repositories. Direkt nachdem du ein Repository geklont hast, ist das Reflog leer, weil noch keine weitere Aktivität stattgefunden hat. git show HEAD@{2.months.ago} funktioniert nur dann, wenn das Projekt mindestens zwei Monate alt ist - wenn du es vor fünf Minuten erst geklont hast, erhältst du keine Ergebnisse.

Ancestry References

Vorfahren Referenzen

The other main way to specify a commit is via its ancestry. If you place a ^ at the end of a reference, Git resolves it to mean the parent of that commit. Suppose you look at the history of your project:

Außerdem kann man Commits über ihre Vorfahren spezifizieren. Wenn du ein ^ ans Ende einer Referenz setzt, schlägt Git den direkten Vorfahren dieses Commits nach. Nehmen wir an, deine Historie sieht so aus:

$ git log --pretty=format:'%h %s' --graph

* 734713b fixed refs handling, added gc auto, updated tests

* d921970 Merge commit 'phedders/rdocs'

|\

| * 35cfb2b Some rdoc changes

* | 1c002dd added some blame and merge stuff

|/

* 1c36188 ignore *.gem

* 9b29157 add open3_detach to gemspec file listThen, you can see the previous commit by specifying HEAD^, which means “the parent of HEAD”:

Du kannst jetzt den vorletzten Commit mit HEAD^ referenzieren, d.h. “den direkten Vorfahren von HEAD”.

$ git show HEAD^

commit d921970aadf03b3cf0e71becdaab3147ba71cdef

Merge: 1c002dd... 35cfb2b...

Author: Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com>

Date: Thu Dec 11 15:08:43 2008 -0800

Merge commit 'phedders/rdocs'You can also specify a number after the ^ — for example, d921970^2 means “the second parent of d921970.” This syntax is only useful for merge commits, which have more than one parent. The first parent is the branch you were on when you merged, and the second is the commit on the branch that you merged in:

Außerdem kannst du nach dem ^ eine Zahl angeben. Beispielsweise heißt d921970^2: “der zweite Vorfahr von d921970”. Diese Syntax ist allerdings nur für Merge Commits nützlich, die mehr als einen Vorfahren haben. Der erste Vorfahr ist der Branch auf dem du dich beim Merge befandest, der zweite ist der Commit auf dem Branch den du gemergt hast.

$ git show d921970^

commit 1c002dd4b536e7479fe34593e72e6c6c1819e53b

Author: Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com>

Date: Thu Dec 11 14:58:32 2008 -0800

added some blame and merge stuff

$ git show d921970^2

commit 35cfb2b795a55793d7cc56a6cc2060b4bb732548

Author: Paul Hedderly <paul+git@mjr.org>

Date: Wed Dec 10 22:22:03 2008 +0000

Some rdoc changesThe other main ancestry specification is the ~. This also refers to the first parent, so HEAD~ and HEAD^ are equivalent. The difference becomes apparent when you specify a number. HEAD~2 means “the first parent of the first parent,” or “the grandparent” — it traverses the first parents the number of times you specify. For example, in the history listed earlier, HEAD~3 would be

Eine andere Vorfahren Spezifikation ist ~. Dies bezieht sich ebenfalls auf den ersten Vorfahren, d.h. HEAD~ und HEAD^ sind äquivalent. Einen Unterschied macht es allerdings, wenn du außerdem eine Zahl angibst. HEAD~2 bedeutet z.B. “der Vorfahr des Vorfahren von HEAD” oder “der n-te Vorfahr von HEAD”. Beispielsweise würde HEAD~3 in der obigen Historie auf den folgenden Commit zeigen:

$ git show HEAD~3

commit 1c3618887afb5fbcbea25b7c013f4e2114448b8d

Author: Tom Preston-Werner <tom@mojombo.com>

Date: Fri Nov 7 13:47:59 2008 -0500

ignore *.gemThis can also be written HEAD^^^, which again is the first parent of the first parent of the first parent:

Dasselbe kannst du mit HEAD^^^ angeben, was wiederum den “Vorfahren des Vorfahren des Vorfahren” referenziert:

$ git show HEAD^^^

commit 1c3618887afb5fbcbea25b7c013f4e2114448b8d

Author: Tom Preston-Werner <tom@mojombo.com>

Date: Fri Nov 7 13:47:59 2008 -0500

ignore *.gemYou can also combine these syntaxes — you can get the second parent of the previous reference (assuming it was a merge commit) by using HEAD~3^2, and so on.

Du kannst diese Schreibweisen auch kombinieren und z.B. auf den zweiten Vorfahren der obigen Referenz mit HEAD~3^2 zugreifen.

Commit Ranges

Commit Reihen

Now that you can specify individual commits, let’s see how to specify ranges of commits. This is particularly useful for managing your branches — if you have a lot of branches, you can use range specifications to answer questions such as, “What work is on this branch that I haven’t yet merged into my main branch?”

Nachdem du jetzt einzelne Commits spezifizieren kannst, schauen wir uns an, wie man auf Commit Reihen zugreift. Dies ist vor allem nützlich, um Branches zu verwalten, z.B. wenn man viele Branches hat und solche Fragen beantworten will wie “Welche Änderungen befinden sich in diesem Branch, die ich noch nicht in meinen Hauptbranch gemergt habe”.

Double Dot

Zwei-Punkte Syntax

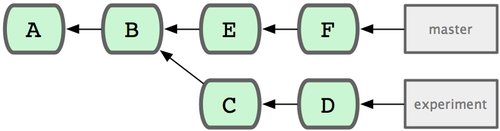

The most common range specification is the double-dot syntax. This basically asks Git to resolve a range of commits that are reachable from one commit but aren’t reachable from another. For example, say you have a commit history that looks like Figure 6-1.

Die gängigste Weise, Commit Reihen anzugeben, ist die Zwei-Punkte Notation. Allgemein gesagt evaluiert Git eine Reihe von Commits, die von einem Commit aus erreichbar sind, nicht aber von einem anderen (xxx ??? xxx). Nehmen wir z.B. an, du hättest eine Commit Historie wie die folgende (Bild 6-1).

Figure 6-1. Example history for range selection.

You want to see what is in your experiment branch that hasn’t yet been merged into your master branch. You can ask Git to show you a log of just those commits with master..experiment — that means “all commits reachable by experiment that aren’t reachable by master.” For the sake of brevity and clarity in these examples, I’ll use the letters of the commit objects from the diagram in place of the actual log output in the order that they would display:

Du willst jetzt herausfinden, welche Änderungen in deinem experiment Branch sind, die noch nicht in den master Branch gemergt wurden. Dann kannst du ein Log dieser Commits mit master..experiment anzeigen, d.h. “alle Commits, die von experiment aus erreichbar sind, aber nicht von master”. Um die folgenden Beispiele ein bißchen abzukürzen und deutlicher zu machen, verwende ich für die Commit Objekte die Buchstaben aus dem Diagramm an stelle der tatsächlichen Log Ausgabe:

$ git log master..experiment

D

CIf, on the other hand, you want to see the opposite — all commits in master that aren’t in experiment — you can reverse the branch names. experiment..master shows you everything in master not reachable from experiment:

Wenn Du allerdings - anders herum - diejenigen Commits anzeigen willst, die in master, aber noch nicht in experiment sind, kannst du die Branch Namen umdrehen: experiment..master zeigt “alles in master, das nicht in experiment enthalten ist”.

$ git log experiment..master

F

EThis is useful if you want to keep the experiment branch up to date and preview what you’re about to merge in. Another very frequent use of this syntax is to see what you’re about to push to a remote:

Dies ist nützlich, wenn du vorhast, den experiment Branch zu aktualisieren, und anzeigen willst, was du dazu mergen wirst. Oder wenn du vorhast, in ein Remote Repository zu pushen und sehen willst, welche Commits betroffen sind:

$ git log origin/master..HEADThis command shows you any commits in your current branch that aren’t in the master branch on your origin remote. If you run a git push and your current branch is tracking origin/master, the commits listed by git log origin/master..HEAD are the commits that will be transferred to the server. You can also leave off one side of the syntax to have Git assume HEAD. For example, you can get the same results as in the previous example by typing git log origin/master.. — Git substitutes HEAD if one side is missing.

Dieser Befehl zeigt dir alle Commits im gegenwärtigen, lokalen Branch, die noch nicht im master Branch des origin Repositories sind. D.h., der Befehl listet diejenigen Commits auf, die auf den Server transferiert würden, wenn du git push benutzt und der aktuelle Branch origin/master trackt. Du kannst mit dieser Syntax außerdem eine Seite der beiden Punkte leer lassen. Git nimmt dann an, du meinst an dieser Stelle HEAD. Z.B. kannst du dieselben Commits wie im vorherigen Beispiel auch mit git log origin/master.. anzeigen lassen. Git fügt dann HEAD auf der rechten Seite ein.

Multiple Points

Mehrfache Punkte (xxx)

The double-dot syntax is useful as a shorthand; but perhaps you want to specify more than two branches to indicate your revision, such as seeing what commits are in any of several branches that aren’t in the branch you’re currently on. Git allows you to do this by using either the ^ character or --not before any reference from which you don’t want to see reachable commits. Thus these three commands are equivalent:

Die Zwei-Punkte Syntax ist eine nützliche Abkürzung, aber möglicherweise willst du mehr als nur zwei Branches angeben, um z.B. herauszufinden, welche Commits in einem beliebigen anderen Branch enthalten sind, ausgenommen in demjenigen, auf dem du dich gerade befindest. Dazu kannst du in Git das ^ Zeichen oder --not verwenden, um Commits auszuschließen, die von den angegebenen Referenzen aus erreichbar sind. D.h., die folgenden drei Befehle sind äquivalent:

$ git log refA..refB

$ git log ^refA refB

$ git log refB --not refAThis is nice because with this syntax you can specify more than two references in your query, which you cannot do with the double-dot syntax. For instance, if you want to see all commits that are reachable from refA or refB but not from refC, you can type one of these:

Das ist praktisch, weil du auf diese Weise mehr als nur zwei Referenzen angeben kannst, was mit der Zwei-Punkte Notation nicht geht. Wenn du beispielsweise alle Commits sehen willst, die von refA oder refB erreichbar sind, nicht aber von refC, dann kannst du folgende (äquivalente) Befehle benutzen:

$ git log refA refB ^refC

$ git log refA refB --not refCThis makes for a very powerful revision query system that should help you figure out what is in your branches.

Damit hast du ein sehr mächtiges System von Abfragen zur Verfügung, mit denen du herausfinden kannst, was in welchen deiner Branches enthalten ist.

Triple Dot

Drei-Punkte Syntax

The last major range-selection syntax is the triple-dot syntax, which specifies all the commits that are reachable by either of two references but not by both of them. Look back at the example commit history in Figure 6-1. If you want to see what is in master or experiment but not any common references, you can run

Die letzte wichtige Syntax, mit der man Commit Reihen spezifizieren kann, ist die Drei-Punkte Syntax, die alle Commits anzeigt, die in einer der beiden Referenzen enthalten sind, aber nicht in beiden. Schau dir noch mal die Commit Historie in Bild 6-1- an. Wenn du diejenigen Commits anzeigen willst, die in den master und experiment Branches, nicht aber in beiden Branches gleichzeitig enthalten sind, dann kannst du folgendes tun:

$ git log master...experiment

F

E

D

CAgain, this gives you normal log output but shows you only the commit information for those four commits, appearing in the traditional commit date ordering.

Dies gibt dir wiederum ein normale log Ausgabe, aber zeigt nur die Informationen dieser vier Commits - wie üblich sortiert nach dem Commit Datum.

A common switch to use with the log command in this case is --left-right, which shows you which side of the range each commit is in. This helps make the data more useful:

Eine nützliche Option für den log Befehl ist in diesem Fall --left-right. Sie zeigt dir an, in welchem der beiden Branches der jeweilige Commit enthalten ist, so daß die Ausgabe noch nützlicher ist:

$ git log --left-right master...experiment

< F

< E

> D

> CWith these tools, you can much more easily let Git know what commit or commits you want to inspect.

Mit diesen Hilfsmitteln kannst du noch einfacher und genauer angeben, welche Commits du nachschlagen willst.