Git Objekte

Git is a content-addressable filesystem. Great. What does that mean? It means that at the core of Git is a simple key-value data store. You can insert any kind of content into it, and it will give you back a key that you can use to retrieve the content again at any time. To demonstrate, you can use the plumbing command hash-object, which takes some data, stores it in your .git directory, and gives you back the key the data is stored as. First, you initialize a new Git repository and verify that there is nothing in the objects directory:

Git ist ein Dateisystem, das Inhalte addressieren kann. Prima. Aber was heißt das? Es bedeutet, daß Git im Kern nichts anderes ist als ein einfacher Key-Value-Store (“Schlüssel-Wert-Speicher”). Du kannst darin jede Art von Inhalt ablegen und Git wird einen Schlüssel dafür zurückgeben, den du dann verwenden kannst, um diesen Inhalt jederzeit nachzuschlagen. Um das auszuprobieren, kannst du den Plumbing Befehl hash-object verwenden. Dieser nimmt einen Inhalt an, speichert ihn in deinem .git Verzeichnis und gibt dir den Schlüssel zurück, unter dem der Inhalt gespeichert wurde. Dazu initialisierst du als erstes ein neues Git Repository und verifizierst, daß das objects Verzeichnis leer ist:

$ mkdir test

$ cd test

$ git init

Initialized empty Git repository in /tmp/test/.git/

$ find .git/objects

.git/objects

.git/objects/info

.git/objects/pack

$ find .git/objects -type f

$Git has initialized the objects directory and created pack and info subdirectories in it, but there are no regular files. Now, store some text in your Git database:

Git hat also ein Verzeichnis objects und darin die pack und info Unterverzeichnisse angelegt, bisher aber keine weiteren Dateien. Als nächsten speichern wir einen Text in dieser Git Datenbank:

$ echo 'test content' | git hash-object -w --stdin

d670460b4b4aece5915caf5c68d12f560a9fe3e4The -w tells hash-object to store the object; otherwise, the command simply tells you what the key would be. --stdin tells the command to read the content from stdin; if you don’t specify this, hash-object expects the path to a file. The output from the command is a 40-character checksum hash. This is the SHA-1 hash — a checksum of the content you’re storing plus a header, which you’ll learn about in a bit. Now you can see how Git has stored your data:

Die Option -w weist git hash-object an, das Objekt zu speichern. Andernfalls würde dir der Befehl lediglich den Schlüssel mitteilen. --stdin weist den Befehl an, den Inhalt von aus der Standardeingabe zu lesen. Wenn du diese Option wegläßt, erwartet der Befehl zusätzlich einen Dateipfad. Die Ausgabe ist eine 40 Zeichen langer SHA-1 Hash, der eine Prüfsumme des gespeicherten Inhaltes darstellt (wir gehen auf diese Hashes gleich noch genauer ein). Git hat jetzt außerdem eine neue Datei in der Datenbank angelegt:

$ find .git/objects -type f

.git/objects/d6/70460b4b4aece5915caf5c68d12f560a9fe3e4You can see a file in the objects directory. This is how Git stores the content initially — as a single file per piece of content, named with the SHA-1 checksum of the content and its header. The subdirectory is named with the first 2 characters of the SHA, and the filename is the remaining 38 characters.

D.h., im objects Verzeichnis befindet sich genau eine Datei. Auf diese Weise Git speichert Inhalte (xxx wieso initially? xxx): in jeweils einer Datei pro Inhalt, referenziert durch den SHA-1 Hash des Inhaltes und seines Headers (xxx Kopfdaten? xxx). Der Name des Unterverzeichnis d6 sind die ersten zwei Zeichen des SHA-1 Hashes und der Dateiname die verbleibenden 38 Zeichen.

You can pull the content back out of Git with the cat-file command. This command is sort of a Swiss army knife for inspecting Git objects. Passing -p to it instructs the cat-file command to figure out the type of content and display it nicely for you:

Mit dem Befehl git cat-file kannst du den jeweiligen Inhalt nachschlagen. Dieser Befehl ist so etwas wie ein Schweizer Taschenmesser, wenn es um Objekte in der Git Datenbank geht. Wenn du die Option -p übergibst, versucht git cat-file, die Art des Inhaltes (z.B. den Dateitypen xxx) herauszufinden und die Anzeige entsprechend lesbar zu formatieren:

$ git cat-file -p d670460b4b4aece5915caf5c68d12f560a9fe3e4

test contentNow, you can add content to Git and pull it back out again. You can also do this with content in files. For example, you can do some simple version control on a file. First, create a new file and save its contents in your database:

Auf diese Weise kannst du also Inhalte zur Datenbank hinzufügen und von dort wieder nachschlagen. Wenn du beispielsweise eine einzelne Datei versionskontrollieren willst, kannst du zunächst die Datei anlegen und den Inhalt in der Datenbank speichern:

$ echo 'version 1' > test.txt

$ git hash-object -w test.txt

83baae61804e65cc73a7201a7252750c76066a30Then, write some new content to the file, and save it again:

Dann kannst du Änderungen vornehmen und die Datei erneut speichern:

$ echo 'version 2' > test.txt

$ git hash-object -w test.txt

1f7a7a472abf3dd9643fd615f6da379c4acb3e3aYour database contains the two new versions of the file as well as the first content you stored there:

Die Datenbank enthält jetzt zwei weitere Versionen der Datei neben dem ursprünglich gespeicherten Inhalt (xxx):

$ find .git/objects -type f

.git/objects/1f/7a7a472abf3dd9643fd615f6da379c4acb3e3a

.git/objects/83/baae61804e65cc73a7201a7252750c76066a30

.git/objects/d6/70460b4b4aece5915caf5c68d12f560a9fe3e4Now you can revert the file back to the first version

Jetzt kannst du die erste Version der Datei mit folgendem Befehl wieder herstellen:

$ git cat-file -p 83baae61804e65cc73a7201a7252750c76066a30 > test.txt

$ cat test.txt

version 1or the second version:

Oder die zweite Version:

$ git cat-file -p 1f7a7a472abf3dd9643fd615f6da379c4acb3e3a > test.txt

$ cat test.txt

version 2But remembering the SHA-1 key for each version of your file isn’t practical; plus, you aren’t storing the filename in your system — just the content. This object type is called a blob. You can have Git tell you the object type of any object in Git, given its SHA-1 key, with cat-file -t:

Sich den SHA-1 Hash für jede Version merken zu müssen, ist allerdings nicht sonderlich praktisch. Außerdem speicherst du nicht den Dateinamen in der Datenbank, sondern lediglich den Inhalt der Datei. Ein solcher Objekttyp wird als “Blob” bezeichnet. Mit git cat-file -t kannst du Git nach dem Typ eines Objektes in der Datenbank fragen:

$ git cat-file -t 1f7a7a472abf3dd9643fd615f6da379c4acb3e3a

blobTree Objects

Baum Objekte

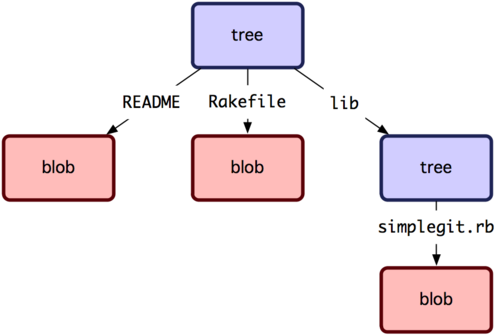

The next type you’ll look at is the tree object, which solves the problem of storing the filename and also allows you to store a group of files together. Git stores content in a manner similar to a UNIX filesystem, but a bit simplified. All the content is stored as tree and blob objects, with trees corresponding to UNIX directory entries and blobs corresponding more or less to inodes or file contents. A single tree object contains one or more tree entries, each of which contains a SHA-1 pointer to a blob or subtree with its associated mode, type, and filename. For example, the most recent tree in the simplegit project may look something like this:

Als nächstes schauen wir uns den Objekttyp “Tree” (Baum) an, der es ermöglicht, Dateinamen zu speichern und Dateien zu gruppieren. Git speichert Inhalte in einer ähnlichen Weise wie das UNIX Dateisystem, allerdings ein bißchen vereinfacht. Sie werden als Tree und Blob Objekte abgelegt, wobei die Trees mit UNIX Verzeichnis Einträgen korrespondieren und Blobs mehr oder weniger mit den inode Einträgen bzw. Datei Inhalten. Ein einzelnes Baum Objekt enthält einen oder mehrere Einträge, von denen jeder ein SHA-1 Hash ist, der wiederum einen Blob oder einen Untertree referenziert. Jeder dieser Einträge verfügt außerdem über einen Modus, Typ und Dateinamen. Beispielsweise sieht das aktuelle Tree Objekt im simplegit Projekt möglicherweise so aus:

$ git cat-file -p master^{tree}

100644 blob a906cb2a4a904a152e80877d4088654daad0c859 README

100644 blob 8f94139338f9404f26296befa88755fc2598c289 Rakefile

040000 tree 99f1a6d12cb4b6f19c8655fca46c3ecf317074e0 libThe master^{tree} syntax specifies the tree object that is pointed to by the last commit on your master branch. Notice that the lib subdirectory isn’t a blob but a pointer to another tree:

Die master^{tree} Syntax spezifiziert, daß wir an dem Tree Objekt interessiert sind, auf das der letzte Commit des master Branches zeigt. Beachte, daß das lib Unterverzeichnis nicht auf ein Blob, sondern wiederum auf einen weiteren Baum zeigt.

$ git cat-file -p 99f1a6d12cb4b6f19c8655fca46c3ecf317074e0

100644 blob 47c6340d6459e05787f644c2447d2595f5d3a54b simplegit.rbConceptually, the data that Git is storing is something like Figure 9-1.

Git speichert Daten also, konzeptuell gesehen, in etwa wie in Bild 9-1 dargestellt.

Figure 9-1. Simple version of the Git data model.

Bild 9-1. Vereinfachte Darstellung des Git Datenmodels.

You can create your own tree. Git normally creates a tree by taking the state of your staging area or index and writing a tree object from it. So, to create a tree object, you first have to set up an index by staging some files. To create an index with a single entry — the first version of your text.txt file — you can use the plumbing command update-index. You use this command to artificially add the earlier version of the test.txt file to a new staging area. You must pass it the --add option because the file doesn’t yet exist in your staging area (you don’t even have a staging area set up yet) and --cacheinfo because the file you’re adding isn’t in your directory but is in your database. Then, you specify the mode, SHA-1, and filename:

Du kannst auch deine eigenen Tree Objekte anlegen. Git erzeugt Trees normalerweise, indem es die Inhalte der Staging Area nimmt und als ein Tree Objekt speichert. D.h., um ein Tree Objekt anzulegen, mußt du zunächst einen Index (d.h. eine Staging Area) erzeugen, indem du einige Dateien hinzufügst. Um einen einzelnen Eintrag in den Index zu schreiben - z.B. die erste version der test.txt Datei - kannst du den Plumbing Befehl git update-index verwenden, der eine frühere Version dieser Datei künstlich zu einer neuen Staging Area hinzufügt. Du mußt ihm die --add Option übergeben, weil die Datei bisher noch nicht in der Staging Area enthalten ist (du hast ja bisher noch überhaupt keine Staging Area aufgesetzt), und die --cacheinfo Option, weil du eine Datei hinzufügst, die sich nicht in deinem Arbeitsverzeichnis befindet (xxx hu? xxx), sondern in der Datenbank. Du gibst außerdem den Modus, SHA-1 Hash und den Dateinamen an:

$ git update-index --add --cacheinfo 100644 \

83baae61804e65cc73a7201a7252750c76066a30 test.txtIn this case, you’re specifying a mode of 100644, which means it’s a normal file. Other options are 100755, which means it’s an executable file; and 120000, which specifies a symbolic link. The mode is taken from normal UNIX modes but is much less flexible — these three modes are the only ones that are valid for files (blobs) in Git (although other modes are used for directories and submodules).

In diesem Fall gibst du als Modus 100644 an, was bedeutet, daß es sich um eine normale Date handelt. Eine ausführbare Datei wäre dagegen 100755 und ein symbolischer Link 120000. Der Modus entspricht normalen UNIX Datei Modi, ist aber weniger flexibel. Die drei genannten Modi sind die einzigen, die in in Git für Dateien (blobs) verwendet werden (es gibt allerdings noch weitere Modi für Verzeichnisse und Submodule xxx).

Now, you can use the write-tree command to write the staging area out to a tree object. No -w option is needed — calling write-tree automatically creates a tree object from the state of the index if that tree doesn’t yet exist:

Jetzt kannst du den Befehl git write-tree verwenden, um die Staging Area als Tree Objekt zu schreiben. Dazu brauchst du die -w Option nicht angeben - git write-tree schreibt automatisch ein Tree Objekt für Einträge der Staging Area, für die es noch keinen Tree gibt:

$ git write-tree

d8329fc1cc938780ffdd9f94e0d364e0ea74f579

$ git cat-file -p d8329fc1cc938780ffdd9f94e0d364e0ea74f579

100644 blob 83baae61804e65cc73a7201a7252750c76066a30 test.txtYou can also verify that this is a tree object:

Um zu überprüfen, daß es wirklich ein Tree Objekt gibt:

$ git cat-file -t d8329fc1cc938780ffdd9f94e0d364e0ea74f579

treeYou’ll now create a new tree with the second version of test.txt and a new file as well:

Jetzt erzeugen wir einen neuen Tree mit der zweiten Version der test.txt Datei sowie eine neue Datei:

$ echo 'new file' > new.txt

$ git update-index test.txt

$ git update-index --add new.txt Your staging area now has the new version of test.txt as well as the new file new.txt. Write out that tree (recording the state of the staging area or index to a tree object) and see what it looks like:

Die Staging Area enthält jetzt eine neue Version der test.txt Datei sowie die neue Datei new.txt. Speichern wir diesen Tree (d.h. den gegenwärtigen Status der Staging Area bzw. des Index als Tree Objekt) und schauen ihn uns an:

$ git write-tree

0155eb4229851634a0f03eb265b69f5a2d56f341

$ git cat-file -p 0155eb4229851634a0f03eb265b69f5a2d56f341

100644 blob fa49b077972391ad58037050f2a75f74e3671e92 new.txt

100644 blob 1f7a7a472abf3dd9643fd615f6da379c4acb3e3a test.txtNotice that this tree has both file entries and also that the test.txt SHA is the “version 2” SHA from earlier (1f7a7a). Just for fun, you’ll add the first tree as a subdirectory into this one. You can read trees into your staging area by calling read-tree. In this case, you can read an existing tree into your staging area as a subtree by using the --prefix option to read-tree:

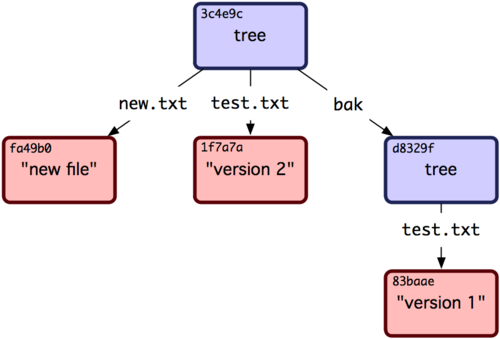

Beachte, daß das Tree Objekt zwei Datei Einträge hat und daß der SHA-1 Hash der test.txt Datei noch derselbe “Version 2” Hash ist wie zuvor (1f7a7a). Fügen wir jetzt den ersten Tree als ein Unterverzeichnis is diesem hier ein. Du kannst einen Tree mit git read-tree in die Staging Area einlesen. In diesem Fall können wir einen bereits existierenden Tree als einen Untertree zur Staging Area hinzufügen, indem wir die --prefix Option verwenden:

$ git read-tree --prefix=bak d8329fc1cc938780ffdd9f94e0d364e0ea74f579

$ git write-tree

3c4e9cd789d88d8d89c1073707c3585e41b0e614

$ git cat-file -p 3c4e9cd789d88d8d89c1073707c3585e41b0e614

040000 tree d8329fc1cc938780ffdd9f94e0d364e0ea74f579 bak

100644 blob fa49b077972391ad58037050f2a75f74e3671e92 new.txt

100644 blob 1f7a7a472abf3dd9643fd615f6da379c4acb3e3a test.txtIf you created a working directory from the new tree you just wrote, you would get the two files in the top level of the working directory and a subdirectory named bak that contained the first version of the test.txt file. You can think of the data that Git contains for these structures as being like Figure 9-2.

Wenn du ein Arbeitsverzeichnis aus diesem neuen Tree Objekt auschecken würdest, würdest du zwei Dateien im Hauptverzeichnis und ein Unterverzeichnis mit dem Namen bak erhalten, in dem sich die erste Version der Datei test.txt befindet. Du kannst dir die Daten, die Git für diese Strukturen speichert, in etwa wie in Bild 9-2 vorstellen.

Figure 9-2. The content structure of your current Git data.

Bild 9-2. Die Datenstruktur des gegenwärtigen Git Repositories.

Commit Objects

Objekte committen

You have three trees that specify the different snapshots of your project that you want to track, but the earlier problem remains: you must remember all three SHA-1 values in order to recall the snapshots. You also don’t have any information about who saved the snapshots, when they were saved, or why they were saved. This is the basic information that the commit object stores for you.

Du hast jetzt drei Trees, die verschiedene Snapshots deines Projektes spezifizieren (xxx), die du nachverfolgen willst. Das ursprüngliche Problem besteht aber weiterhin: du mußt alle drei SHA-1 Hash Werte erinnern, um wieder an die Snapshots zu kommen. Ebenso fehlen dir die Informationen darüber, wer die Snapshots gespeichert hat, wann sie gespeichert wurden und warum. Dies sind die drei Hauptinformationen, die ein Commit Objekt für uns speichert.

To create a commit object, you call commit-tree and specify a single tree SHA-1 and which commit objects, if any, directly preceded it. Start with the first tree you wrote:

Um ein Commit Objekt anzulegen, verwendest du den Befehl git commit-tree, spezifizierst einen einzelnen Tree SHA-1 Hash und welche Commit Objekte (sofern vorhanden) die direkten Vorgänger sind. Fangen wir damit an, den ersten Tree, den du angelegt hast, zu committen:

$ echo 'first commit' | git commit-tree d8329f

fdf4fc3344e67ab068f836878b6c4951e3b15f3dNow you can look at your new commit object with cat-file:

Du kannst diesen Commit jetzt mit git cat-file nachschlagen:

$ git cat-file -p fdf4fc3

tree d8329fc1cc938780ffdd9f94e0d364e0ea74f579

author Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com> 1243040974 -0700

committer Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com> 1243040974 -0700

first commitThe format for a commit object is simple: it specifies the top-level tree for the snapshot of the project at that point; the author/committer information pulled from your user.name and user.email configuration settings, with the current timestamp; a blank line, and then the commit message.

Das Format für ein Commit Objekt ist einfach: es besteht aus dem toplevel Tree für den Snapshot des Projektes zum gegebenen Zeitpunkt, die Autor und ggf. Committer Information (jeweils entsprechend deiner user.name und user.email Konfiguration) und dem Timestamp. Dann folgen eine leere Zeile und die Commit Meldung.

Next, you’ll write the other two commit objects, each referencing the commit that came directly before it:

Als nächstes speichern wir die beiden anderen Commit Objekte und referenzieren jeweils den vorhergehenden Commit:

$ echo 'second commit' | git commit-tree 0155eb -p fdf4fc3

cac0cab538b970a37ea1e769cbbde608743bc96d

$ echo 'third commit' | git commit-tree 3c4e9c -p cac0cab

1a410efbd13591db07496601ebc7a059dd55cfe9Each of the three commit objects points to one of the three snapshot trees you created. Oddly enough, you have a real Git history now that you can view with the git log command, if you run it on the last commit SHA-1:

Jedes der drei Commit Objekte zeigt auf einen der drei Snapshopt Trees, die du zuvor gespeichert hattest. Es mag dich überraschen, aber du hast jetzt bereits eine vollständige Git Historie, die du mit dem git log inspizieren kannst, indem du den letzten Commit SHA-1 Hash angibst:

$ git log --stat 1a410e

commit 1a410efbd13591db07496601ebc7a059dd55cfe9

Author: Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com>

Date: Fri May 22 18:15:24 2009 -0700

third commit

bak/test.txt | 1 +

1 files changed, 1 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

commit cac0cab538b970a37ea1e769cbbde608743bc96d

Author: Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com>

Date: Fri May 22 18:14:29 2009 -0700

second commit

new.txt | 1 +

test.txt | 2 +-

2 files changed, 2 insertions(+), 1 deletions(-)

commit fdf4fc3344e67ab068f836878b6c4951e3b15f3d

Author: Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com>

Date: Fri May 22 18:09:34 2009 -0700

first commit

test.txt | 1 +

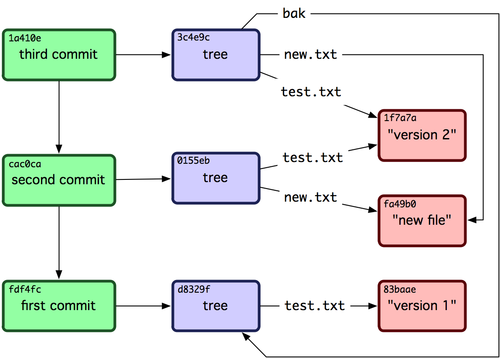

1 files changed, 1 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)Amazing. You’ve just done the low-level operations to build up a Git history without using any of the front ends. This is essentially what Git does when you run the git add and git commit commands — it stores blobs for the files that have changed, updates the index, writes out trees, and writes commit objects that reference the top-level trees and the commits that came immediately before them. These three main Git objects — the blob, the tree, and the commit — are initially stored as separate files in your .git/objects directory. Here are all the objects in the example directory now, commented with what they store:

Fantastisch, oder? Du hast jetzt sämtliche low-level Operationen durchgeführt, die eine vollständige Git Historie aufbauen, ohne aber irgendwelche Git Frontend Befehle (xxx) zu verwenden. Im wesentlichen ist das derselbe Prozeß, der im Hintergrund stattfindet, wenn du die Befehle git add und git commit ausführst. Sie speichern Blobs für die Dateien, die du hinzugefügt oder geändert hast, aktualisieren den Index (d.h. die Staging Area), speichern Trees und legen Commit Objekte an, die die toplevel Trees und Commits referenzieren, die ihnen unmittelbar vorhergingen. Diese drei Hauptobjekte - Blob, Tree und Commit - werden zunächst als separate Dateien im .git/objects Verzeichnis gespeichert. Hier ist eine Liste aller Objekte, die sich in unserem Beispiel Repository jetzt in der Datenbank befinden - jeweils mit einem Kommentar darüber, was sie speichern:

$ find .git/objects -type f

.git/objects/01/55eb4229851634a0f03eb265b69f5a2d56f341 # tree 2

.git/objects/1a/410efbd13591db07496601ebc7a059dd55cfe9 # commit 3

.git/objects/1f/7a7a472abf3dd9643fd615f6da379c4acb3e3a # test.txt v2

.git/objects/3c/4e9cd789d88d8d89c1073707c3585e41b0e614 # tree 3

.git/objects/83/baae61804e65cc73a7201a7252750c76066a30 # test.txt v1

.git/objects/ca/c0cab538b970a37ea1e769cbbde608743bc96d # commit 2

.git/objects/d6/70460b4b4aece5915caf5c68d12f560a9fe3e4 # 'test content'

.git/objects/d8/329fc1cc938780ffdd9f94e0d364e0ea74f579 # tree 1

.git/objects/fa/49b077972391ad58037050f2a75f74e3671e92 # new.txt

.git/objects/fd/f4fc3344e67ab068f836878b6c4951e3b15f3d # commit 1If you follow all the internal pointers, you get an object graph something like Figure 9-3.

Wenn man all diese Zeiger auflöst, erhält man einen Objekt Graphen wie den folgenden (Bild 9-3).

Figure 9-3. All the objects in your Git directory.

Bild 9-3. Die Objekte im Beispielrepository.

Object Storage

Objekt Speicher

I mentioned earlier that a header is stored with the content. Let’s take a minute to look at how Git stores its objects. You’ll see how to store a blob object — in this case, the string “what is up, doc?” — interactively in the Ruby scripting language. You can start up interactive Ruby mode with the irb command:

Wir haben kurz erwähnt, daß zusammen mit einem Inhalt ein Header gespeichert wird. Schauen wir uns also genauer an, wie genau Git Objekte speichert. Du wirst sehen, wie ein Blob Objekt - in diesem Fall der String “what is up, doc?” (xxx übersetzen? xxx) gespeichert wird. Dazu nuten wir den interaktiven Ruby Modus, den du mit dem irb Befehl starten kannst:

$ irb

>> content = "what is up, doc?"

=> "what is up, doc?"Git constructs a header that starts with the type of the object, in this case a blob. Then, it adds a space followed by the size of the content and finally a null byte:

Git erzeugt einen Header, der mit dem Objekt Typ beginnt, in diesem Fall ist das ein Blob. Dann folgt ein Leerzeichen, die Anzahl der Zeichen des Inhalts und schließlich ein Nullbyte.

>> header = "blob #{content.length}\0"

=> "blob 16\000"Git concatenates the header and the original content and then calculates the SHA-1 checksum of that new content. You can calculate the SHA-1 value of a string in Ruby by including the SHA1 digest library with the require command and then calling Digest::SHA1.hexdigest() with the string:

Git fügt diesen Header mit dem ursprünglichen Inhalt zusammen und kalkuliert aus dem Ergebnis die SHA-1 Prüfsumme (Hash). Du kannst einen SHA-1 Hash in Ruby berechnen, indem du die SHA1 digest Bibliothek mit require einbindest und dann Digest::SHA1.hexdigest() mit dem String ausführst:

>> store = header + content

=> "blob 16\000what is up, doc?"

>> require 'digest/sha1'

=> true

>> sha1 = Digest::SHA1.hexdigest(store)

=> "bd9dbf5aae1a3862dd1526723246b20206e5fc37"Git compresses the new content with zlib, which you can do in Ruby with the zlib library. First, you need to require the library and then run Zlib::Deflate.deflate() on the content:

Git komprimiert den neuen Inhalt (d.h. inklusive des Headers) mit zlib. In Ruby kannst du dazu die zlib Bibliothek verwenden, indem du wiederum zuerst die Bibliothek mit require einbindest und dann Zlib::Deflate.deflate() mit dem Inhalt aufrufst:

>> require 'zlib'

=> true

>> zlib_content = Zlib::Deflate.deflate(store)

=> "x\234K\312\311OR04c(\317H,Q\310,V(-\320QH\311O\266\a\000_\034\a\235"Finally, you’ll write your zlib-deflated content to an object on disk. You’ll determine the path of the object you want to write out (the first two characters of the SHA-1 value being the subdirectory name, and the last 38 characters being the filename within that directory). In Ruby, you can use the FileUtils.mkdir_p() function to create the subdirectory if it doesn’t exist. Then, open the file with File.open() and write out the previously zlib-compressed content to the file with a write() call on the resulting file handle:

Schließlich schreibst du den zlib-komprimierten Inhalt in eine Datei auf der Festplatte. Dazu bestimmst du den Pfad, an den die Datei gespeichert wird (die ersten beiden Zeichen für das Unterverzeichnis und die verbleibenden 38 Zeichen für den Dateinamen). In Ruby kannst du die Funktion FileUtils.mkdir_p() verwenden, um Unterverzeichnisse anzulegen, die noch nicht existieren. Dann öffnest die Datei mit File.open() und schreibst den komprimierten Inhalt mit write() in die Datei:

>> path = '.git/objects/' + sha1[0,2] + '/' + sha1[2,38]

=> ".git/objects/bd/9dbf5aae1a3862dd1526723246b20206e5fc37"

>> require 'fileutils'

=> true

>> FileUtils.mkdir_p(File.dirname(path))

=> ".git/objects/bd"

>> File.open(path, 'w') { |f| f.write zlib_content }

=> 32That’s it — you’ve created a valid Git blob object. All Git objects are stored the same way, just with different types — instead of the string blob, the header will begin with commit or tree. Also, although the blob content can be nearly anything, the commit and tree content are very specifically formatted.

Das ist alles - du hast jetzt ein valides Git Blob Objekt geschrieben. Git Objekte werden immer in dieser Weise gespeichert, lediglich mit verschiedenen Typen, d.h. anstelle des Strings “blob” wird der Header mit “commit” oder “tree” anfangen. Außerdem sind Commit und Tree Inhalte auf eine sehr spezifische Weise formatiert, während Blobs beliebige Inhalte sein können.