Git Referenzen

You can run something like git log 1a410e to look through your whole history, but you still have to remember that 1a410e is the last commit in order to walk that history to find all those objects. You need a file in which you can store the SHA-1 value under a simple name so you can use that pointer rather than the raw SHA-1 value.

Du kannst Befehle wie git log 1a410e ausführen, um die Commit Historie zu inspizieren, aber dazu mußt du dir jeweils merken, daß 1a410e der jeweils letzte Commit ist. Um diese SHA-1 Hashes mit einfacheren, verständlichen Namen zu referenzieren, verwendet Git weitere Dateien, in denen die Namen für Hashes gespeichert sind.

In Git, these are called “references” or “refs”; you can find the files that contain the SHA-1 values in the .git/refs directory. In the current project, this directory contains no files, but it does contain a simple structure:

Diese Namen werden in Git intern als “references” oder “refs” bezeichnet. Du kannst diese Dateien, die SHA-1 Hashes enthalten, im .git/refs Verzeichnis finden. In unserem gegenwärtigen Projekt enthält dieses Verzeichnis noch keine Dateien, aber eine simple Verzeichnisstruktur:

$ find .git/refs

.git/refs

.git/refs/heads

.git/refs/tags

$ find .git/refs -type f

$To create a new reference that will help you remember where your latest commit is, you can technically do something as simple as this:

Um jetzt eine neue Referenz anzulegen, die dir dabei hilft, dich zu erinnern, wo sich dein letzten Commit befindet, könntest du, technisch gesehen, folgendes tun:

$ echo "1a410efbd13591db07496601ebc7a059dd55cfe9" > .git/refs/heads/masterNow, you can use the head reference you just created instead of the SHA-1 value in your Git commands:

Jetzt kannst du diese “head” Referenz anstelle des SHA-1 Wertes in allen möglichen Git Befehlen verwenden:

$ git log --pretty=oneline master

1a410efbd13591db07496601ebc7a059dd55cfe9 third commit

cac0cab538b970a37ea1e769cbbde608743bc96d second commit

fdf4fc3344e67ab068f836878b6c4951e3b15f3d first commitYou aren’t encouraged to directly edit the reference files. Git provides a safer command to do this if you want to update a reference called update-ref:

Allerdings ist es nicht empfehlenswert, die Referenz Dateien direkt zu bearbeiten. Git stellt einen sichereren Befehl dafür zur Verfügung, den Befehl git update-ref:

$ git update-ref refs/heads/master 1a410efbd13591db07496601ebc7a059dd55cfe9That’s basically what a branch in Git is: a simple pointer or reference to the head of a line of work. To create a branch back at the second commit, you can do this:

Im Prinzip ist das alles, was einen Branch in Git ausmacht: ein simpler Zeiger oder eine Referenz auf den jeweiligen Kopf (xxx head xxx) einer Serie von Commits (xxx ??? xxx). Um einen neuen Branch anzulegen, der vom zweiten Commit aus verzweigt, kannst du folgendes tun:

$ git update-ref refs/heads/test cac0caYour branch will contain only work from that commit down:

Dein Branch beginnt jetzt beim zweiten Commit:

$ git log --pretty=oneline test

cac0cab538b970a37ea1e769cbbde608743bc96d second commit

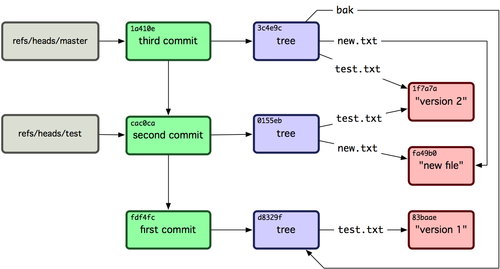

fdf4fc3344e67ab068f836878b6c4951e3b15f3d first commitNow, your Git database conceptually looks something like Figure 9-4.

Die Git Datenbank unseres Beispielrepositories ist jetzt wie folgt strukturiert:

Figure 9-4. Git directory objects with branch head references included.

Bild 9-4. Git Verzeichnis Objekte mit Branch Head Referenzen.

When you run commands like git branch (branchname), Git basically runs that update-ref command to add the SHA-1 of the last commit of the branch you’re on into whatever new reference you want to create.

Wenn du Befehle wie git branch (branchname) verwendest, führt Git intern im wesentlichen den update-ref Befehl aus, um den SHA-1 Hash des letzten Commits des jeweils gegenwärtigen Branches mit dem gegebenen Namen zu referenzieren.

The HEAD

Der HEAD

The question now is, when you run git branch (branchname), how does Git know the SHA-1 of the last commit? The answer is the HEAD file. The HEAD file is a symbolic reference to the branch you’re currently on. By symbolic reference, I mean that unlike a normal reference, it doesn’t generally contain a SHA-1 value but rather a pointer to another reference. If you look at the file, you’ll normally see something like this:

Die Frage ist jetzt: wenn du git branch (branchname) ausführst, woher weiß Git den SHA-1 des letzten Commits? Die Antwort ist: aus der HEAD Datei. Diese Datei ist eine symbolische Referenz auf den jeweiligen Branch, auf dem du dich gerade befindest. Mit “symbolischer Referenz” meine ich, daß sie (anders als eine “normale” Referenz) keinen SHA-1 Hash enthält, sondern statt dessen auf eine andere Referenz zeigt. Wenn Du die HEAD Datei ansiehst, findest du normalerweise etwas wie:

$ cat .git/HEAD

ref: refs/heads/masterIf you run git checkout test, Git updates the file to look like this:

Wenn du jetzt git checkout test ausführst, wird Git die Datei aktualisieren, so daß sie so aussieht:

$ cat .git/HEAD

ref: refs/heads/testWhen you run git commit, it creates the commit object, specifying the parent of that commit object to be whatever SHA-1 value the reference in HEAD points to.

Wenn du git commit ausführst, erzeugt Git das Commit Objekt und verwendet als Parent des Commit Objektes den jeweiligen Wert der Referenz auf die HEAD zeigt.

You can also manually edit this file, but again a safer command exists to do so: symbolic-ref. You can read the value of your HEAD via this command:

Du kannst diese Datei manuell bearbeiten, aber es Git verfügt wiederum über einen sichereren Befehl, um das zu tun: git symbolic-ref. Du kannst den Wert des HEAD mit Hilfe des folgenden Befehls lesen:

$ git symbolic-ref HEAD

refs/heads/masterYou can also set the value of HEAD:

Und so kannst du ihn setzen:

$ git symbolic-ref HEAD refs/heads/test

$ cat .git/HEAD

ref: refs/heads/testYou can’t set a symbolic reference outside of the refs style:

Du kannst den Befehl allerdings nicht verwenden, um eine Referenz außerhalb von refs zu setzen:

$ git symbolic-ref HEAD test

fatal: Refusing to point HEAD outside of refs/Tags

Tags

You’ve just gone over Git’s three main object types, but there is a fourth. The tag object is very much like a commit object — it contains a tagger, a date, a message, and a pointer. The main difference is that a tag object points to a commit rather than a tree. It’s like a branch reference, but it never moves — it always points to the same commit but gives it a friendlier name.

Wir haben jetzt Gits drei Haupt Objekttypen besprochen, aber es gibt noch einen vierten. Das Tag Objekt ist dem Commit Objekt sehr ähnlich: es enthält einen Tagger (xxx), ein Datum, eine Meldung und eine Referenz auf ein anderes Objekt. Der Hauptunterschied besteht darin, daß ein Tag Objekt auf einen Commit zeigt und nicht auf einen Tree. Ein Tag ist in dieser Hinsicht also ähnlich einem Branch, aber er bewegt sich nie, sondern zeigt immer auf denselben Commit und gibt ihm damit einen netteren Namen.

As discussed in Chapter 2, there are two types of tags: annotated and lightweight. You can make a lightweight tag by running something like this:

Wie wir schon in Kapitel 2 besprochen haben, gibt es zwei Typen von Tags: “annotierte” und “einfache”. Du kannst einen einfachen Tag wie folgt anlegen:

$ git update-ref refs/tags/v1.0 cac0cab538b970a37ea1e769cbbde608743bc96dThat is all a lightweight tag is — a branch that never moves. An annotated tag is more complex, however. If you create an annotated tag, Git creates a tag object and then writes a reference to point to it rather than directly to the commit. You can see this by creating an annotated tag (-a specifies that it’s an annotated tag):

Das ist alles, woraus ein einfacher Tag besteht: einem Branch, der sich nie bewegt. Ein annotierter Tag ist komplexer. Wenn du einen annotierten Tag anlegst, erzeugt Git ein Tag Objekt und speichert eine Referenz, die darauf zeigt, statt direkt auf den Commit zu zeigen. Du kannst das sehen, wenn du einen annotierten Tag anlegst (-a bewirkt, daß wir einen annotierten Tag erhalten):

$ git tag -a v1.1 1a410efbd13591db07496601ebc7a059dd55cfe9 –m 'test tag'Here’s the object SHA-1 value it created:

Das erzeugt den folgenden Objekt SHA-1 Hash:

$ cat .git/refs/tags/v1.1

9585191f37f7b0fb9444f35a9bf50de191beadc2Now, run the cat-file command on that SHA-1 value:

Jetzt wendest du den git cat-file Befehl auf diesen SHA-1 Hash an:

$ git cat-file -p 9585191f37f7b0fb9444f35a9bf50de191beadc2

object 1a410efbd13591db07496601ebc7a059dd55cfe9

type commit

tag v1.1

tagger Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com> Sat May 23 16:48:58 2009 -0700

test tagNotice that the object entry points to the commit SHA-1 value that you tagged. Also notice that it doesn’t need to point to a commit; you can tag any Git object. In the Git source code, for example, the maintainer has added their GPG public key as a blob object and then tagged it. You can view the public key by running

Beachte, daß der der object Wert auf den commit SHA-1 zeigt, den du getaggt hast, und daß die tags/v1.1 Referenz nicht direkt auf den Commit zeigt, sondern auf das Tag Objekt. In Git kannst du jedes beliebige Objekt taggen. Im Git Quellcode z.B. befindet sich der öffentliche GPG Schlüssel des Projektbetreibers als ein Blob Objekt, sowie ein Tag, der darauf zeigt. Auf diese Weise kannst den Schlüssel so anzeigen, indem du den folgenden Befehl im Git Quellcode Repository ausführst:

$ git cat-file blob junio-gpg-pubin the Git source code. The Linux kernel also has a non-commit-pointing tag object — the first tag created points to the initial tree of the import of the source code.

Der Linux Kernel hat also ein Tag Objekt, das nicht auf einen Commit zeigt - der erste Tag (xxx) zeigt auf den ursprünglichen Tree mit dem Import des Quellcodes (xxx what? xxx).

Remotes

Externe Referenzen

The third type of reference that you’ll see is a remote reference. If you add a remote and push to it, Git stores the value you last pushed to that remote for each branch in the refs/remotes directory. For instance, you can add a remote called origin and push your master branch to it:

Der dritte Referenztyp ist die externe Referenz (“remote reference”). Wenn du einen externen Server (“remote”) definierst und dorthin pushst, merkt sich Git den zuletzt gepushten Commit für jeden Branch im refs/remotes Verzeichnis. Bespielsweise fügst du einen externen Server origin hinzu und pushst deinen master Branch dorthin:

$ git remote add origin git@github.com:schacon/simplegit-progit.git

$ git push origin master

Counting objects: 11, done.

Compressing objects: 100% (5/5), done.

Writing objects: 100% (7/7), 716 bytes, done.

Total 7 (delta 2), reused 4 (delta 1)

To git@github.com:schacon/simplegit-progit.git

a11bef0..ca82a6d master -> masterThen, you can see what the master branch on the origin remote was the last time you communicated with the server, by checking the refs/remotes/origin/master file:

Dann kannst du herausfinden, in welchem Zustand sich der master Branch auf dem origin Server zuletzt befand (d.h. als du das letzte Mal mit ihm kommuniziert hast), indem du die Datei refs/remotes/origin/master anschaust:

$ cat .git/refs/remotes/origin/master

ca82a6dff817ec66f44342007202690a93763949Remote references differ from branches (refs/heads references) mainly in that they can’t be checked out. Git moves them around as bookmarks to the last known state of where those branches were on those servers.

Externe Referenzen unterscheiden sich von Branches (refs/heads) hauptsächlich dadurch, daß man sie nicht auschecken kann. Git verwendet sie quasi als Lesezeichen für den zuletzt bekannten Status, in dem sich die Branches auf externen Servern jeweils befanden.